_

GROVE EXCAVATIONS AUTUMN 1999,

PORTLAND, DORSET

Background

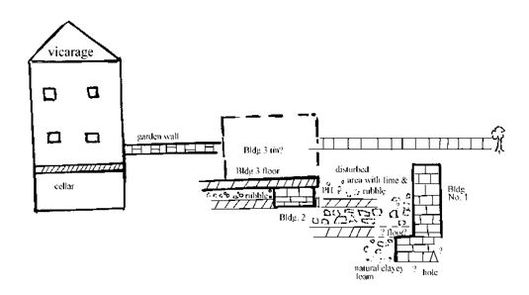

During trial excavations in May 1999 in the front garden of the Old St. Peter’s Vicarage in the Grove, Portland, some evidence was found of a very early substantial, well-built stone wall associated with a floor of lime plaster. Overlying this was evidence of one or two more recent buildings , also with floors of lime plaster on top of limestone rubble. These all visibly pre-dated the vicarage, as was also revealed in a gully excavated by the wall of the vicarage for new sewage pipes in 1998. It was not possible to obtain more details of any of the structures found in May as there were too many restrictions caused by domestic pipes and other features.

From September to November the Association of Portland Archaeology carried out further excavations in another slightly larger area of the front garden. On this occasion it was realised that there were, in fact, three older buildings partly on top of each other in the grounds, pre-dating the vicarage. No certain documentary or map references to any of them exist.

Description of Finds

The whole site appears to have been extensively disturbed on several occasions in Victorian times and, unfortunately, no finds have been made which definitely date the earlier buildings. Because of the severe disturbance everywhere and into all layers, even the stratigraphical interpretations of the site are not fully reliable, with the exception of the most recent building phase, which will be referred to as Building 3.

Large quantities of coke and iron clinker suggests the carry on of smithy work in the grounds. It is possible that this work also relates to out-of-doors activities of the men who used Building 3 or else there is a possibility that the site was also used as an outdoor working area in earlier Victorian times by the convicts who had built the breakwater. The officer in charge of the convicts then lived at the house adjacent the vicarage, now known as Ivybanks.

The most recent of the three buildings excavated, was a temporary building (Building 3), probably of tin and had a floor of compact lime plaster, which overlay a layer of stone rubble which was used to level of the unevenness of the site, created by the still older buildings. The archaeologists found a corner post of this building and a definite corner of its floor. The indications were that the rest of this building continued eastwards into the grounds of the adjacent St. Peter’s church.

The presence of substantial green Cornish slate in the debris on its floor, is a reasonably clear indication that this building was a workshop associated with the building of the church, the only building in the neighbourhood with green slate (as opposed to the more common grey Welsh slate). The workmen appear to have made extensive use of the whole of the ground round the workshop and, in doing so, drastically disturbed all earlier remains on the site.

It was found that the corner of the workshop was actually laid down over part of the foundation wall of an earlier building, which will be referred to as Building 2. (Note: Reference to Building 1 or 2 does not necessarily have priority or chronological implications). This building must have been very substantial as the foundations are about two thirds of a metre (2ft) wide. The stones in this do not appear to have been carefully tooled but have only been roughly shaped to form the (approximately) straight line of the wall, which slightly varies in width along the length as excavated. This floor was also associated with a layer of compact lime plaster on top of an under-floor layer of limestone rubble. No archaeological indications were found of the date or the nature of this building.

The mystery at the Grove, however, goes even deeper. Below the building, mentioned above, the archaeologists have found a layer of rubble and then another floor of lime plaster, belonging to another stone wall (to be referred to as Building 1)

Background

During trial excavations in May 1999 in the front garden of the Old St. Peter’s Vicarage in the Grove, Portland, some evidence was found of a very early substantial, well-built stone wall associated with a floor of lime plaster. Overlying this was evidence of one or two more recent buildings , also with floors of lime plaster on top of limestone rubble. These all visibly pre-dated the vicarage, as was also revealed in a gully excavated by the wall of the vicarage for new sewage pipes in 1998. It was not possible to obtain more details of any of the structures found in May as there were too many restrictions caused by domestic pipes and other features.

From September to November the Association of Portland Archaeology carried out further excavations in another slightly larger area of the front garden. On this occasion it was realised that there were, in fact, three older buildings partly on top of each other in the grounds, pre-dating the vicarage. No certain documentary or map references to any of them exist.

Description of Finds

The whole site appears to have been extensively disturbed on several occasions in Victorian times and, unfortunately, no finds have been made which definitely date the earlier buildings. Because of the severe disturbance everywhere and into all layers, even the stratigraphical interpretations of the site are not fully reliable, with the exception of the most recent building phase, which will be referred to as Building 3.

Large quantities of coke and iron clinker suggests the carry on of smithy work in the grounds. It is possible that this work also relates to out-of-doors activities of the men who used Building 3 or else there is a possibility that the site was also used as an outdoor working area in earlier Victorian times by the convicts who had built the breakwater. The officer in charge of the convicts then lived at the house adjacent the vicarage, now known as Ivybanks.

The most recent of the three buildings excavated, was a temporary building (Building 3), probably of tin and had a floor of compact lime plaster, which overlay a layer of stone rubble which was used to level of the unevenness of the site, created by the still older buildings. The archaeologists found a corner post of this building and a definite corner of its floor. The indications were that the rest of this building continued eastwards into the grounds of the adjacent St. Peter’s church.

The presence of substantial green Cornish slate in the debris on its floor, is a reasonably clear indication that this building was a workshop associated with the building of the church, the only building in the neighbourhood with green slate (as opposed to the more common grey Welsh slate). The workmen appear to have made extensive use of the whole of the ground round the workshop and, in doing so, drastically disturbed all earlier remains on the site.

It was found that the corner of the workshop was actually laid down over part of the foundation wall of an earlier building, which will be referred to as Building 2. (Note: Reference to Building 1 or 2 does not necessarily have priority or chronological implications). This building must have been very substantial as the foundations are about two thirds of a metre (2ft) wide. The stones in this do not appear to have been carefully tooled but have only been roughly shaped to form the (approximately) straight line of the wall, which slightly varies in width along the length as excavated. This floor was also associated with a layer of compact lime plaster on top of an under-floor layer of limestone rubble. No archaeological indications were found of the date or the nature of this building.

The mystery at the Grove, however, goes even deeper. Below the building, mentioned above, the archaeologists have found a layer of rubble and then another floor of lime plaster, belonging to another stone wall (to be referred to as Building 1)

_

_

SUMMARY OF EXCAVATIONS IN THE

GROUNDS OF ST. STEPHEN’S VICARAGE, GROVE, PORTLAND. By Susann Palmer, Director of A.P.A.

The full detailed report of our Association’s work in the Grove has been published in the Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society; a summary of some of the reasoning and conclusions in that report is given below.

Some comments which were recently published in the Free Portland News indicates that there are still people on Portland who believe that so much of the Grove area has been excavated in the distant past that nothing of archaeological interest can possibly remain there. A.P.A’s recent work in the grounds of the vicarage clearly illustrate that even this part of the Island can still hold surprises.

Resumè of findings

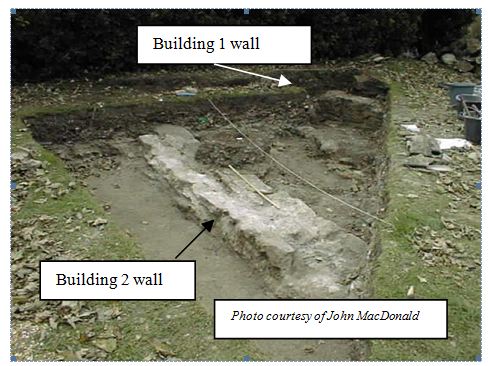

Remains of two walls were found: Wall number one was part of a very substantial wall standing about 1.5m high, .45m wide, and consisted of good quality cut stone; it had a stone ledge at the base which was possibly the support for a floor or else the beginning of a basement level. Wall 2 had only the foundation remaining, about 30cms wide and also originally part of a substantial building. We concluded that Building 2 was the oldest and that its walls may have been robbed of its stone, perhaps for use in the later Building one. Building 3 overlay these two buildings, with a big post-hole cutting into the side of Wall 2. We concluded that Building 3 was almost certainly associated with the workers who had built the adjacent St. Peter’s church.

It was impossible to establish a clear profile of the site stratigraphy because of the severe disturbances of the original terrain since the late 19th century. There was a virtual absence of dateable finds associated with the earlier walls, possibly again because of all the numerous later disturbances. One small piece of Roman pottery was found and one or two bits of medieval pottery but these were not regarded as adequate to be reliable dating evidence.

Background details

In June 1998 Mr. Michael McCormick Smith , the present owner of the Old St. Peter’s Vicarage in the Grove, Portland, had a trench dug in his front garden to have a new sewage pipe laid. He alerted members of A.P.A. to the fact that at one point in the trench the remains of a wall were noticed and at another point there was a level compact surface of rubble and lime plaster. It was evident that these features had been disturbed by previous pipe laying through the property.

Very detailed Deeds for the house are held by the owner and are dated 21.6.1889. They indicate that the ground was sold by the Admiralty Commission to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for the building of the vicarage under various acts of Parliament issued during the reigns of George III, George IV and Queen Victoria. The plans with the deed indicate the church of St. Peters, which was built in 1872 by convicts. The plans also indicate the adjacent house to the west, then known as Quarry House but now known as Ivybanks. This house was built just before 1848 for the engineer who was in charge of the building of the breakwater by convicts. These men were housed in a temporary building in the vicinity of the present Young Offenders Institute. The grounds of the vicarage are indicated as completely blank.

The implications were, therefore, that the remains noticed in the excavations must either long pre-date the vicarage and the church or else must have been built after the maps of 1889 were completed. The latter option can be ruled out as the walls of the ruined buildings visibly, went in the direction of the present Grove road and would have been, at least, partly under the road and partly under the wall between the church and the vicarage . The road is known to have been made at the turn of this century as access to the (permanent) building of the prison and neighbouring houses; it was previously just a track.

Archival and other Research

During the excavation work, a survey was made of all visible boundary walls in the neighbourhood in the hope of finding clues to the enigma of the structures in the vicarage garden. It was regarded as extremely puzzling that such substantial buildings can disappear without leaving any traces or even records of their previous existence. However, a study of the northern boundary walls of the Old Vicarage as indicated on the 1889 Deeds and an on-site survey of them, revealed that the lower half of them are much older than the upper half. The boundary walls of St. Peter’s Church at one point cut through this wall, but then diverts away from it, indicating that this boundary wall pre-dates the church.

A survey of all local existing boundary walls, carried out by Rod Wild of A.P.A., combined with a research of recorded or remembered previously existing boundary walls, suggests that at some stage in the more distant past there may have been a sub-circular property enclosure in the Grove. It may be possible that it was the boundary wall of a large, previously unknown estate, encompassing the grounds of the present church and vicarage as well as the buildings of which the remains are now being excavated. A local who has grown up in the Grove, recollects that as a child they used to play on an earthern bank, topped by a low dry-stone rubble wall in an open field which ran approximately east to west, now across the road from St. Peter’s Church in the grounds of the present local electric sub-station and a terrace of small houses. The bank was an estimated 4.5 meters (15 ft) high and consisted primarily of a red clay, which stained clothing which came into contact with it. It is known that in the nearby Admiralty Quarries there used to be a deposit of red ochreous Late Pleistocene clay which had produced mammalia remains (Palmer 1998); the clay in this bank could, therefore, either represent a continuation of that deposit or, else the clay to build the bank may have been derived from there. The latter alternative is unlikely – clay would have been dug from the immediate locale of the bank.

All known early maps of Portland in the Dorset County Archives, the Dorset County Museum and Weymouth Reference Library were studied, as well as copies of early maps of the Isle of Portland known to be in the British Museum. None of them showed any buildings or structures in the Grove area prior to the building of the house Ivybanks and the church of St Peters and the vicarage at the end of the 19th century.

Lord Burleigh’s map of c1539 (the so-called Henry VIII map. British Museum Cotton Ms Aug. A.1 31/33) shows two tall buildings (or towers) adjacent two beacons on the Verne Heights but they are not clearly placed and should not definitely be related to the finds in the Grove area. It is, however, vaguely possible that they may have some relevance to the two early ruins in the Grove, even though on the map there is no indications as to the nature of the illustrated two buildings.

The full detailed report of our Association’s work in the Grove has been published in the Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society; a summary of some of the reasoning and conclusions in that report is given below.

Some comments which were recently published in the Free Portland News indicates that there are still people on Portland who believe that so much of the Grove area has been excavated in the distant past that nothing of archaeological interest can possibly remain there. A.P.A’s recent work in the grounds of the vicarage clearly illustrate that even this part of the Island can still hold surprises.

Resumè of findings

Remains of two walls were found: Wall number one was part of a very substantial wall standing about 1.5m high, .45m wide, and consisted of good quality cut stone; it had a stone ledge at the base which was possibly the support for a floor or else the beginning of a basement level. Wall 2 had only the foundation remaining, about 30cms wide and also originally part of a substantial building. We concluded that Building 2 was the oldest and that its walls may have been robbed of its stone, perhaps for use in the later Building one. Building 3 overlay these two buildings, with a big post-hole cutting into the side of Wall 2. We concluded that Building 3 was almost certainly associated with the workers who had built the adjacent St. Peter’s church.

It was impossible to establish a clear profile of the site stratigraphy because of the severe disturbances of the original terrain since the late 19th century. There was a virtual absence of dateable finds associated with the earlier walls, possibly again because of all the numerous later disturbances. One small piece of Roman pottery was found and one or two bits of medieval pottery but these were not regarded as adequate to be reliable dating evidence.

Background details

In June 1998 Mr. Michael McCormick Smith , the present owner of the Old St. Peter’s Vicarage in the Grove, Portland, had a trench dug in his front garden to have a new sewage pipe laid. He alerted members of A.P.A. to the fact that at one point in the trench the remains of a wall were noticed and at another point there was a level compact surface of rubble and lime plaster. It was evident that these features had been disturbed by previous pipe laying through the property.

Very detailed Deeds for the house are held by the owner and are dated 21.6.1889. They indicate that the ground was sold by the Admiralty Commission to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for the building of the vicarage under various acts of Parliament issued during the reigns of George III, George IV and Queen Victoria. The plans with the deed indicate the church of St. Peters, which was built in 1872 by convicts. The plans also indicate the adjacent house to the west, then known as Quarry House but now known as Ivybanks. This house was built just before 1848 for the engineer who was in charge of the building of the breakwater by convicts. These men were housed in a temporary building in the vicinity of the present Young Offenders Institute. The grounds of the vicarage are indicated as completely blank.

The implications were, therefore, that the remains noticed in the excavations must either long pre-date the vicarage and the church or else must have been built after the maps of 1889 were completed. The latter option can be ruled out as the walls of the ruined buildings visibly, went in the direction of the present Grove road and would have been, at least, partly under the road and partly under the wall between the church and the vicarage . The road is known to have been made at the turn of this century as access to the (permanent) building of the prison and neighbouring houses; it was previously just a track.

Archival and other Research

During the excavation work, a survey was made of all visible boundary walls in the neighbourhood in the hope of finding clues to the enigma of the structures in the vicarage garden. It was regarded as extremely puzzling that such substantial buildings can disappear without leaving any traces or even records of their previous existence. However, a study of the northern boundary walls of the Old Vicarage as indicated on the 1889 Deeds and an on-site survey of them, revealed that the lower half of them are much older than the upper half. The boundary walls of St. Peter’s Church at one point cut through this wall, but then diverts away from it, indicating that this boundary wall pre-dates the church.

A survey of all local existing boundary walls, carried out by Rod Wild of A.P.A., combined with a research of recorded or remembered previously existing boundary walls, suggests that at some stage in the more distant past there may have been a sub-circular property enclosure in the Grove. It may be possible that it was the boundary wall of a large, previously unknown estate, encompassing the grounds of the present church and vicarage as well as the buildings of which the remains are now being excavated. A local who has grown up in the Grove, recollects that as a child they used to play on an earthern bank, topped by a low dry-stone rubble wall in an open field which ran approximately east to west, now across the road from St. Peter’s Church in the grounds of the present local electric sub-station and a terrace of small houses. The bank was an estimated 4.5 meters (15 ft) high and consisted primarily of a red clay, which stained clothing which came into contact with it. It is known that in the nearby Admiralty Quarries there used to be a deposit of red ochreous Late Pleistocene clay which had produced mammalia remains (Palmer 1998); the clay in this bank could, therefore, either represent a continuation of that deposit or, else the clay to build the bank may have been derived from there. The latter alternative is unlikely – clay would have been dug from the immediate locale of the bank.

All known early maps of Portland in the Dorset County Archives, the Dorset County Museum and Weymouth Reference Library were studied, as well as copies of early maps of the Isle of Portland known to be in the British Museum. None of them showed any buildings or structures in the Grove area prior to the building of the house Ivybanks and the church of St Peters and the vicarage at the end of the 19th century.

Lord Burleigh’s map of c1539 (the so-called Henry VIII map. British Museum Cotton Ms Aug. A.1 31/33) shows two tall buildings (or towers) adjacent two beacons on the Verne Heights but they are not clearly placed and should not definitely be related to the finds in the Grove area. It is, however, vaguely possible that they may have some relevance to the two early ruins in the Grove, even though on the map there is no indications as to the nature of the illustrated two buildings.

A map of_mid-18th century has the words ‘Black Fryors’ written at an

angle in the general area of the Grove, near where the vicarage is now, but without any indications as to whether it

refers to a specific area or feature or

just to a vaguely defined area .

Mrs C. King Warry (1913) refers to the names of Monks Plot and Priory (as in the present Priory Corner) on Portland. She points out that John Leland (1535-1543) in his Itinerary paid a visit to the old church (the first St. Andrew’s) adjacent Bow and Arrow Castle (Rufus Castle) on the Island; he stated that he had been informed that ‘Sum say that in tymes past ther was another paroch chirch in the isle, but I there lernid no certente of it’ . She appears to imply that there could have been a connection between the two place names and this earlier church. This would, of course, mean that by the middle of the 16th century that earlier church was not visible any more and not known as a church, i.e. it may have been in ruins by then.

In an unpublished manuscript The High Places of Portland (Dorset County Museum Boxfile 5) Mrs King Warry also refers to the Grove area as a place of possible sanctity, being approximately midway between two areas which contained stone circles, now both destroyed (at the old Manor Farm and in the garden of the Governor of the Young Offenders Institute).

Mrs C. King Warry (1913) refers to the names of Monks Plot and Priory (as in the present Priory Corner) on Portland. She points out that John Leland (1535-1543) in his Itinerary paid a visit to the old church (the first St. Andrew’s) adjacent Bow and Arrow Castle (Rufus Castle) on the Island; he stated that he had been informed that ‘Sum say that in tymes past ther was another paroch chirch in the isle, but I there lernid no certente of it’ . She appears to imply that there could have been a connection between the two place names and this earlier church. This would, of course, mean that by the middle of the 16th century that earlier church was not visible any more and not known as a church, i.e. it may have been in ruins by then.

In an unpublished manuscript The High Places of Portland (Dorset County Museum Boxfile 5) Mrs King Warry also refers to the Grove area as a place of possible sanctity, being approximately midway between two areas which contained stone circles, now both destroyed (at the old Manor Farm and in the garden of the Governor of the Young Offenders Institute).

_ As archaeologists, we believe that in ancient folk-lore there was often a ‘fire where there is smoke’ , i.e. there is

a chance of some factual basis to many

an old tale - even if the facts may turn

out to be a little warped! So, maybe we

will keep on pursuing the Grove story.

The Blackfriars (Dominican Order) had established a church in Melcombe Regis (now included in Weymouth) in c1418. This is known to have been the last new religious house to be established in England before the Dissolution in the following 16th century and its establishment originally met with some opposition and is referred to in many publications (e.g. Ellis, 1829; Hutchins 3rd ed; Long, 1937; Palmer, 1888; Victoria County History; 1st ed. 1774, 2nd ed. 1803). Interestingly, the Rev. Owen Watson, rector of Portland, had an interest in the Dominican Order and made a request that a tomb for him should be built in the grounds of the Order. It is not known where it was to be built, whether it was built nor whether he was buried in it when he died c1538. It could be feasible to argue that, as he had an interest in the Order, there must have been some presence of monks of the Order on the Isle or that there could have been a building related to the Blackfriars on the Island or else that he had invited them to build one.

It must be stressed that there is no documentary proof for the existence of such an early church or even priory or friary on Portland. If such a building had existed, it is possible that it was not in use for very long prior to the dissolution and hence did not make it into the local records or onto maps of the time (unless, of course, the enigmatic buildings on the Henry VIII map does refer to some such religious building(s) in the Grove).

Summary and Conclusions The builders and users of the temporary Building 3 were without doubt the men who had built the present St. Peter’s Church. They had extensively interfered with the older buildings on the site and appears to have dug holes all over the place, possibly for throwing their rubbish in. The builders of the vicarage must have utilised the same ground space for doing their work in.

It is not possible to make any definite observations about the stratigraphical relationship of the discovered features to each other. Building 3 is the most recent and can be securely dated to 1872 –c1875; it is not known whether it was demolished after the building of the church, but it is possible that it was still standing, at least in part, when the vicarage was built or that the same ground space was then again utilised.

Buildings 1 and 2 cannot be part of one and the same building; the angle between the two walls is too acute to make this feasible. It seems likely that Building 2 (as represented by the foundation wall only) is the older. As far as could be ascertained, the wall of Building 1 appears to have been dug through the limeplaster floor layers of Building 2; this confusion is due to the fact that later holes, numerous backfillings and ground-levelling had destroyed all stratigraphical evidence and due to the fact that it was not possible to dig further down to the original natural soil level below the foundations of Building 1 because of limitations of working space.

Both Buildings 1 and 2 were of a very substantial nature and both were almost certainly well-built and of an elegant appearance. It is highly unlikely that they were buildings of a humble domestic nature, as also suggested by the total absence of objects of domestic or personal refuse. It seems feasible to accept that Buildings 2 and 1 were early buildings of an ecclesiatic nature - either one or two churches and/or a priory/friary - which somehow or other fits into the above explained scenario of the Island’s religious history. It seems certain that these buildings were already ruins by the end of the eighteenth century, if not long before.

The most surprising element of the whole research is the fact that very substantial buildings were built, demolished and had totally disappeared from sight during historical periods, without leaving any documentary trace whatsoever of their existence on the Isle. It suggests that there could be a lot more finds of archaeological importance to be made on the Isle.

The results of the research can be regarded as filling a very important gap in the history of Portland, even though the precise details of the significance of the remains are not yet known.

It is to be hoped that in the future further information will become available as a result of other excavations in the neighbourhood or as a result of further, at present overlooked, documentary evidence.

The Blackfriars (Dominican Order) had established a church in Melcombe Regis (now included in Weymouth) in c1418. This is known to have been the last new religious house to be established in England before the Dissolution in the following 16th century and its establishment originally met with some opposition and is referred to in many publications (e.g. Ellis, 1829; Hutchins 3rd ed; Long, 1937; Palmer, 1888; Victoria County History; 1st ed. 1774, 2nd ed. 1803). Interestingly, the Rev. Owen Watson, rector of Portland, had an interest in the Dominican Order and made a request that a tomb for him should be built in the grounds of the Order. It is not known where it was to be built, whether it was built nor whether he was buried in it when he died c1538. It could be feasible to argue that, as he had an interest in the Order, there must have been some presence of monks of the Order on the Isle or that there could have been a building related to the Blackfriars on the Island or else that he had invited them to build one.

It must be stressed that there is no documentary proof for the existence of such an early church or even priory or friary on Portland. If such a building had existed, it is possible that it was not in use for very long prior to the dissolution and hence did not make it into the local records or onto maps of the time (unless, of course, the enigmatic buildings on the Henry VIII map does refer to some such religious building(s) in the Grove).

Summary and Conclusions The builders and users of the temporary Building 3 were without doubt the men who had built the present St. Peter’s Church. They had extensively interfered with the older buildings on the site and appears to have dug holes all over the place, possibly for throwing their rubbish in. The builders of the vicarage must have utilised the same ground space for doing their work in.

It is not possible to make any definite observations about the stratigraphical relationship of the discovered features to each other. Building 3 is the most recent and can be securely dated to 1872 –c1875; it is not known whether it was demolished after the building of the church, but it is possible that it was still standing, at least in part, when the vicarage was built or that the same ground space was then again utilised.

Buildings 1 and 2 cannot be part of one and the same building; the angle between the two walls is too acute to make this feasible. It seems likely that Building 2 (as represented by the foundation wall only) is the older. As far as could be ascertained, the wall of Building 1 appears to have been dug through the limeplaster floor layers of Building 2; this confusion is due to the fact that later holes, numerous backfillings and ground-levelling had destroyed all stratigraphical evidence and due to the fact that it was not possible to dig further down to the original natural soil level below the foundations of Building 1 because of limitations of working space.

Both Buildings 1 and 2 were of a very substantial nature and both were almost certainly well-built and of an elegant appearance. It is highly unlikely that they were buildings of a humble domestic nature, as also suggested by the total absence of objects of domestic or personal refuse. It seems feasible to accept that Buildings 2 and 1 were early buildings of an ecclesiatic nature - either one or two churches and/or a priory/friary - which somehow or other fits into the above explained scenario of the Island’s religious history. It seems certain that these buildings were already ruins by the end of the eighteenth century, if not long before.

The most surprising element of the whole research is the fact that very substantial buildings were built, demolished and had totally disappeared from sight during historical periods, without leaving any documentary trace whatsoever of their existence on the Isle. It suggests that there could be a lot more finds of archaeological importance to be made on the Isle.

The results of the research can be regarded as filling a very important gap in the history of Portland, even though the precise details of the significance of the remains are not yet known.

It is to be hoped that in the future further information will become available as a result of other excavations in the neighbourhood or as a result of further, at present overlooked, documentary evidence.